Participatory approaches towards GEP design and implementation guide

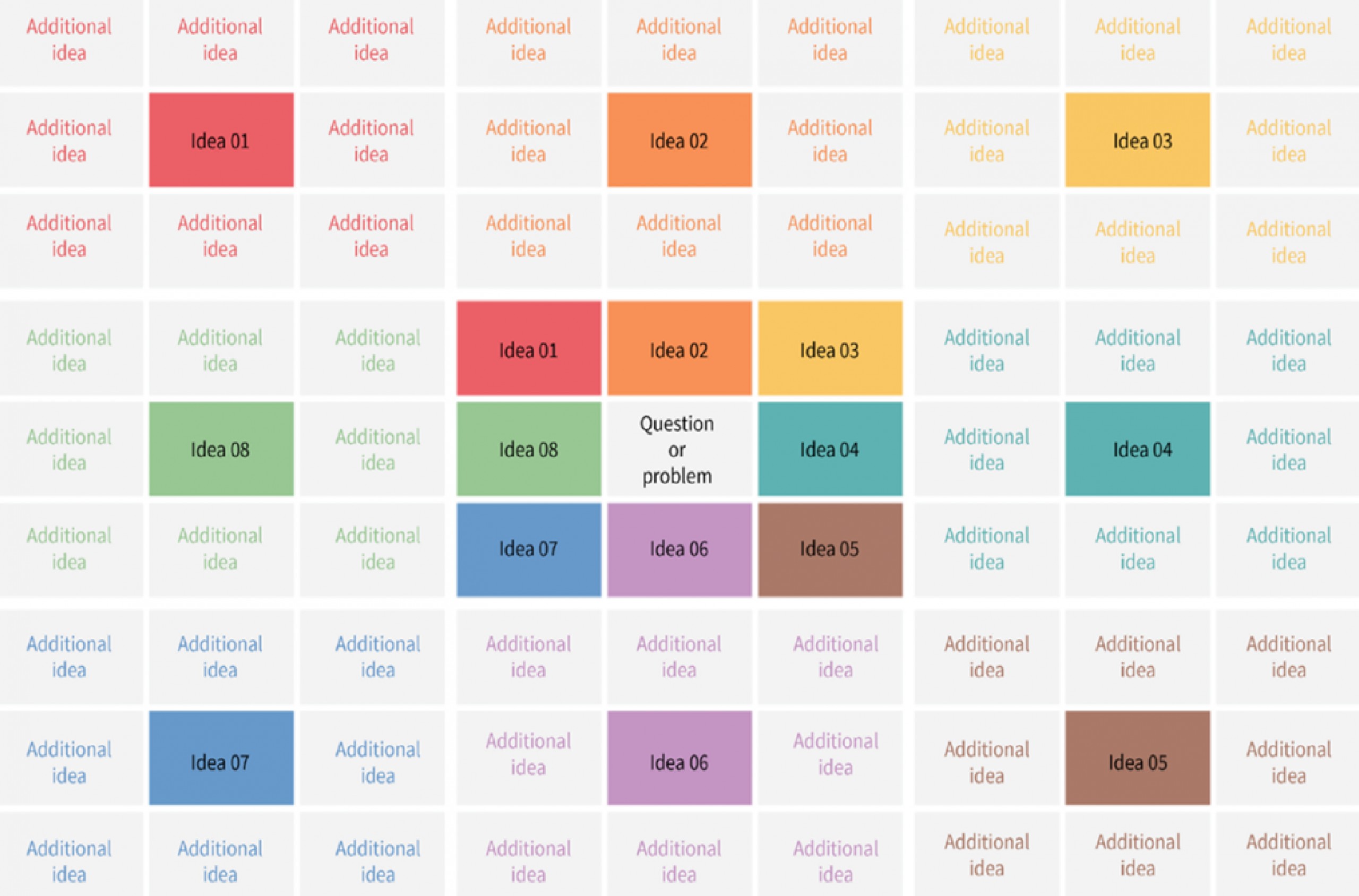

Based on the experience of the SUPERA, Yellow Window developed a guide on how to facilitate participation from stakeholders in the design and implementation of Gender equality Plans (GEPs). The document builds on the one hand on a project deliverable that was made available to the SUPERA core teams in each GEP implementing institution at the start of the project, and on the other hand on the actual experience of using these techniques. It aims at providing guidance to all those who will implement Gender Equality Plans on how to proceed with this type of techniques.

This publication is meant as a reference document and guide for all who intend to use participatory techniques. The target of this publication are the members of the core team in charge of the GEP inside an institution, as well as those acting as change facilitators.

Download the Participatory approaches towards GEP design and implementation SUPERA guide [file .pdf]

Visit the web page dedicated to participatory techniques